What are the key threats facing gold mining operations in the Sahel region?

This article is an extract from a longer report, available to download in full from the Intelligence Fusion website — click here to get the full guide.

The central Sahel region of Africa, comprising Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, is home to some of the world’s richest gold deposits. Mali, for instance, is Africa’s third largest producer of gold, and exported a record 65.2 tonnes of gold in 2020. It is also one of the least developed regions of the world, with fragile states, severe levels of poverty and a growing security crisis involving armed rebel groups, warring jihadist factions and state security forces that has followed the 2012 crisis in Mali, despite the intervention of foreign forces. The large quantities of gold in the region have made the central Sahel an attractive destination for large mining companies, and there are a significant number of industrial mining sites that have been established, particularly in Mali and Burkina Faso — but in an area of significant instability, high levels of violence and fragile state control, there are a number of threats that face any company wishing to base their operations in the region. This report will highlight several key factors that pose a threat to gold mining in the central Sahel region — some of which pose a direct threat to gold mining companies, and others that threaten their activity indirectly through fuelling instability in the region. By demonstrating these threats, and the ways in which they can fuel each other, this report will also aim to highlight the importance of situational awareness when operating in areas of risk, and how accurate threat intelligence can allow companies to minimise this risk as much as possible.

Overview

The central Sahel is one of the most underdeveloped regions in the world, with the three countries that principally make up the region — Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger — ranked 184th, 182nd and 189th of 189 respectively in the UN Human Development Index. Poverty is widespread in these three countries; a World Food Programme report dated 3rd April 2021 states that 14.4 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance in Burkina Faso (3.5 million), Mali (7 million) and Niger (3 million) — 6.5 million people are projected to be in severe food insecurity. Compounding the problem is the insecurity in the region, which has led to more than 1.8 million people being internally displaced (IDPs) in Burkina Faso (1.1 million), Mali (347,000) and Niger (300,300).

A number of armed conflicts and insurgencies have raged in the region since the 2012 uprising in northern Mali. At the time of writing these are principally comprised by separate jihadist movements involving Al Qaeda and Islamic State affiliated militants in northern, central and eastern Mali, north eastern Burkina Faso and western Niger; and Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) militants operating in the Lake Chad Basin of south eastern Niger, and across its borders with Nigeria and Chad. This report will focus on the former, given its proximity to areas of gold mining operations in the central Sahel.

The significant gold reserves found in the region have made it an attractive proposition for industrial mining companies; according to EITI estimates, Mali has an estimated 800 metric tons of gold reserves, Burkina Faso has 154.2 metric tons, and Niger an estimated 65 metric tons. There are an estimated 13 gold mines operated by multinational companies in Mali, primarily in the southwest of the country; in Burkina Faso, there are 11 different active industrial gold mines, most of which started within the last ten years. There is currently only one industrial gold mining company operating in Niger, located near its western border with Burkina Faso, however, according to the World Bank, Turkish and Chinese owned exploration companies have reportedly invested into gold mining exploration in the country.

There are also significant numbers of informal, ‘artisanal’ mines, some of which operate with government issued permits, many of which operate illegally — these mines can represent a vital source of income for millions of people in such an impoverished region, despite often incredibly difficult working conditions. Child labour is reportedly high in artisanal mines; according to one report, in Mali, an estimated 20% of labourers are children, in Burkina Faso this could be as high as 30–50%, while in Niger there could be around 22,000 children working in its artisanal mines. Mines can reach depths of 100 metres, often hand-dug, and conditions are characterised by squalor and lack of access to basic amenities. They can nevertheless be fairly sophisticated operations, with the use of heavy equipment commonplace at illegal mining sites, as well as explosives for extraction, and chemicals such as mercury and cyanide — often with little regard for the surrounding environment. They are also a driver of migration, causing a “gold rush” that has been accelerated by the discovery of a new gold seam in 2012.

Threats to gold mining in the Sahel

Jihadist groups and terrorism in the Sahel

There are a number of different jihadist groups that operate in the central Sahel, but they can broadly be said to be belonging to two different coalitions — the Al Qaeda affiliated Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), and the Islamic State affiliated Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS) — although there are also a number of independently operating groups, such as Ansarul Islam in Burkina Faso. JNIM officially formed as a coalition in 2017 when disparate jihadist groups including the Saharan branch of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Al Mourabitoun, Ansar Dine and the Macina Liberation Front (MLF, also known as Katiba Macina) merged together, and pledged their allegiance to Al Qaeda in a video featuring members of each of these groups — including Ansar Dine leader Iyad ag Ghali, and Katiba Macina leader Amadou Kouffa. ISGS on the other hand formed in 2016 as a splinter from Al Mourabitoun, when now ISGS leader Adnan Abu Walid al Sahrawi swore allegiance to the Islamic State. These two groups initially appeared to co-exist in a somewhat uneasy peace, in contrast to the international rivalry between Al Qaeda and IS groups around the world, but from late 2019 onwards violent clashes between the two began to be recorded, and the groups now frequently carry out armed attacks against each other, as well as civilians and state-affiliated forces.

These groups had been operating in northern Mali since the early part of the decade, but violent extremism has been spreading since 2012 to the extent that they together now operate in large areas of northern and central Mali, including the Kidal region, inner Niger Delta and regions of Mopti and Segou, and across Mali’s borders into Niger and Burkina Faso; the extremist threat has especially escalated further from 2018 onwards, causing Burkina Faso to declare a state of emergency on 31st December 2018. Terrorist activity is now particularly prevalent in, but certainly not limited to, the Liptako-Gourma tri-border region of the three countries, comprising central and eastern Mali, north and eastern Burkina Faso, and western Niger.

These groups carry out frequent attacks on both military and civilian targets. These attacks frequently result in very heavy casualties, often hundreds of people at a time, with the number of terrorism-related deaths increasing as time goes by. In January 2020, the United Nations Security Council reported that there were over 4,000 casualties from terrorist attacks in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger in 2019, a fivefold increase from an estimated 770 deaths reported in 2016 — with Burkina Faso going from 80 reported deaths in 2016 to over 1,800 in 2019. In April 2021, ISS Africa reported more than 300 deaths in Western Niger alone so far this year — this includes an attack in the Tillaberi region near Mali on 2nd January, in which ISGS militants raided two villages, killing over 100 people and wounding at least 26 more. Even more recently to the time of writing, Burkina Faso witnessed the worst atrocity in terms of civilian deaths since 2015 on 5th June 2021, where gunmen, likely JNIM or ISGS, attacked the village of Solhan, Yagha Province, targeting an artisanal mining site there, and killing at least 160 civilians.

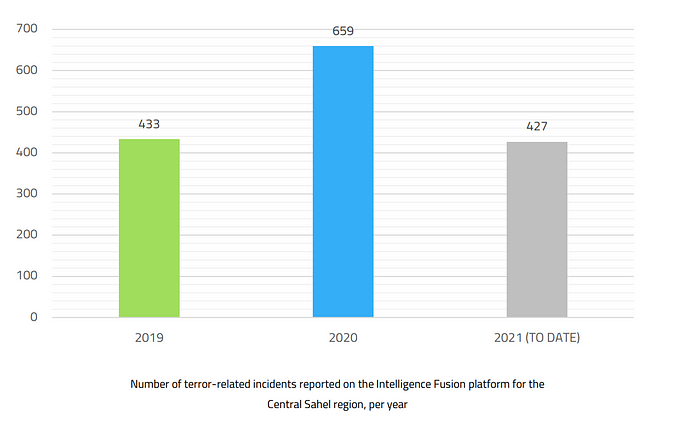

This increasing intensity of violent extremism is reflected on the Intelligence Fusion platform — in 2019 we mapped 433 incidents tagged as terrorism in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger; in 2020 it was 659; so far in 2021 we’ve already mapped 427, with at least 1,859 people (security forces, civilians and insurgents) reported to have been killed during terrorist incidents.

This spread of jihadist activity has meant that areas that were relatively free of terrorism just a few years ago are now finding themselves increasingly vulnerable — and this includes industrial mining areas. While jihadist groups have so far refrained from launching direct attacks on major mining sites, many areas that they operate in are experiencing increasing levels of terrorist activity, putting supply chains, logistical routes and workers at risk. Both JNIM and ISGS carry out frequent ambushes, IEDs and armed attacks — and these are becoming more and more prevalent in areas near industrial mining operations. The most notable of these was the complex attack carried out in the Est region of Burkina Faso on 6th November 2019, targeting a convoy of vehicles transporting SEMAFO mining employees, contractors and suppliers. In the attack the leading vehicle was hit by an IED, before gunmen then opened fire on the convoy — at least 37 people were killed, with another 60 wounded. The attack took place on the R28 regional road 40km from the Boungou gold mine, then operated by SEMAFO, and is to date the most high-profile terrorist incident to directly target industrial mining operations. However, it came after a series of other terror-related incidents in the region, and even on the same route, in the months preceding it.

On 30th November 2018, a police vehicle escorting SEMAFO workers to the Boungou site was also struck by an IED, killing four police and a civilian driver. Following that, there were a number of terrorist incidents that took place within 50km of the Boungou site, leading up to the convoy attack. On 17th April 2019, unidentified gunmen attacked the Boulmontchangou market in Tapoa province; two days later gunmen set the primary school of nearby Boulmontiaga village on fire — both of these incidents took place in villages along the D8 department road that connects to the east of the R28. Even more notable was an attack on 23rd May 2019. A military attachment was ambushed by armed men while on its way to Nakortougo, travelling along the R28 road — the same road as the SEMAFO convoy attack. This build up of incidents demonstrates that, while the SEMAFO attack may have been notable for its direct impact on the mining industry, it was part of a wider pattern of jihadist violence that was spreading through the area, something that could be identified and tracked using threat intelligence software.

As outlined above, since the attack in November 2019, this jihadist violence has spread even further, placing mining operations at a greater level of risk, particularly those in the Liptako-Gourma areas of Burkina Faso, where jihadist activity is especially high, and where some of the largest gold mines in the region operate — such as the Boungou mine in the Est province, and the Essakane mine in the Sahel province. While JNIM and ISGS are primarily focused on fighting with security forces, self-defence militias and, since 2019, each other, they are also opportunists, and frequently carry out ambushes and abductions, with foreign nationals particularly attractive targets for kidnap for ransom. In January 2019, for instance, Kirk Woodman, a Canadian geologist employed by Progress Minerals, was abducted and killed by gunmen in northern Burkina Faso, near the border with Niger. In January 2020, Kimar Akoliya was released after nearly two years in captivity — Akoliya is the son of Akoliya Patel, the Indian owner of Balaji mining group, who operate the Inata mine in northern Burkina Faso. He had set off for Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou, from the mine with two colleagues when they were kidnapped in September 2018.

More recently, on 8th April 2021, French journalist Olivier Dubois was abducted in Gao, Mali. Dubois had arranged an interview with Abdallah Ag Albakaye, a JNIM leader, but did not return. On 26th April 2021, two Spanish journalists, an Irish citizen and a Burkinabe soldier were abducted and killed by JNIM attackers when travelling with an anti-poaching patrol. In October 2020, JNIM released four high-profile hostages, including a French national and two Italians, and Malian opposition leader Soumaila Cisse, after the Malian government released over 200 militants, including a number of top jihadi leaders, and reportedly paid a large ransom of up to €30 million. Typical ransom fees for a foreign national are much higher than for locals, and have historically been a lucrative source of funding for terrorist groups in the region. A 2014 New York Times report stated that Al Qaeda were netting up to $10 million per person, with AQIM being paid $91.5 million between 2008 and 2014. Any foreign nationals employed by mining companies should therefore be considered as a potential target for kidnap by jihadist groups.

Given the continued spread of violence, and its proximity to many industrial mining sites, it is of vital importance to closely monitor the activity of jihadist groups such as JNIM and ISGS if operating in this region, take steps to ensure the safety and security of mining sites, and carry out regular route threat assessments on any necessary logistical and travel routes.